by Danielle Gilman

Collaboration is an essential element of first-year writing seminars at UConn. Students spend the semester exploring project-based inquiries through a series of course moves designed to facilitate ongoing exchange with their classmates and instructors. In addition to encouraging students to perform experiential research, participate in and contribute to public discussions & debates, and create interactivity with a range of audiences, these course moves make our seminars particularly well suited to collaboration beyond the classroom. And so, during this year’s FYW Winter Welcome, instructors gathered to discuss opportunities to build relationships between our classes and offices and organizations across and beyond our campuses.

Having joined the program a little over a year ago as an APiR and WPA, I thought my perspective on this topic might be a useful one; I have spent a good amount of time these last months building new relationships and tuning into existing campus and community networks both in Stamford and across our campus system. My goal as the facilitator of this workshop was not to offer an expert perspective on each and every potential campus and community partnership available to our instructors but to explore together what it might look like to open up our first-year writing classes to these sorts of opportunities.

My own teaching brings together my interests in literary studies, writing studies, and archival studies—and I look within and between these spaces to inform my pedagogy and to support key learning outcomes in my classroom, whether that means working through adopting a multimodal framework for writing and communication; learning about the fundamentals of primary source literacy; or more broadly composing rhetorically savvy work that articulates the scope and value of research to multiple audiences. Much of my current research and work in the classroom considers how to effectively integrate archival primary sources into first-year writing classes to support this type of skill development. And so, the cross-campus and community relationships I’ve worked to develop usually emerge out of the archive.

At my previous institution, for instance, I worked over a series of semesters during the pandemic with an archival educator to create asynchronous programming that would draw on digitized materials within the university’s collections. In recent years, I’ve also worked with archivists at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York to facilitate workshops and create primary source sets that introduce students to archival research. And this semester, I’m working with Kara Flynn, UConn’s Archives Education & Outreach Coordinator on a virtual classroom workshop for my 1007 students that will introduce digitized materials held in our Archives and Special Collections as well as engage them in discussions about the ethics of preservation, controlled vocabularies, and what it means to think critically with an archive.

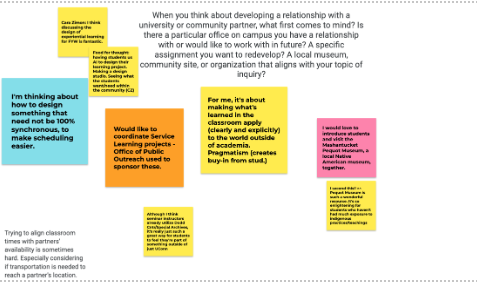

At the start of this winter’s workshop, I asked participants to begin by considering a few guiding questions: When you think about developing a potential relationship with a university or community partner, what first comes to mind? Is there a particular office on campus you have a relationship with or would like to work with? Are there any local museums, community sites, or organizations that align with your topic of inquiry? The answers received indicated a range of potential opportunities and interests (see figure 1).

Fig 1. Responses to the Winter Welcome Jamboard

Some instructors indicated an interest in building out service-learning courses, for instance, while others considered how they might partner with experts at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center for an assignment or unit. One commonality in our discussion that afternoon was a shared desire to approach these potential collaborations pragmatically—making sure, as one participant notes above, that we are “making what’s learned in the classroom apply (clearly and explicitly) to the world outside of academia” via these learning experiences.

In this vein, I spent a portion of our workshop sharing a few suggestions and strategies I’ve adopted in my own work to ensure that potential partnerships and collaborations are reasonable in scope, of value to my students and their learning outcomes, and support my professional goals as well.

Time is key: work one semester ahead and plan on piloting over one year.

It’s not always realistic to plan on teaching the same course over a series of semesters, but in an ideal world, I would allot three semesters to building out a new campus or community relationship. Over the summer, I sketch out what I’d like an assignment or unit to look like, and I reach out to the relevant person or office. It can be difficult to have those conversations during the semester because we’re all so stretched for time. That point is situationally dependent, of course. When I work with archivists in private archives, for example, summer is often their busy time because researchers are visiting the reading room while off from teaching. Even still, what’s generally worked for me is using the summer to draft plans, establish initial contact, and schedule planning conversations in person or via Zoom. Then, I put into practice the assignment or unit in the fall, tinker with any concerns over winter break, and run a more polished, final version in the spring.

Isolate a particular course move or learning goal you’d like to explore.

What I’ve heard most often when approaching a campus office or professional in the community for the first time is that it’s helpful for them to receive clear, specific information about the learning goals you’re attempting to meet. If you’re able to articulate in initial meetings what skill(s) you’d like students to develop, or even share a syllabus, reading list, or assignment handout, that information is often more valuable to a collaborator than providing them with a list of specific materials you’d like them to source for your students.

Consider how to approach questions of access and modality.

As someone who works extensively within and around archives, I had to revise my approach to a lot of my work during the pandemic, for instance. And while I’d never advocate for emergency remote teaching as a useful learning experience, revising coursework and approaching relationships and partnerships for hybrid and remote modalities did encourage me to think more critically about access points in my classroom even after we returned to face-to-face instruction.

Don’t limit yourself to creating new partnerships exclusively on your own campus. At Stamford, we have great access to community organizations in Fairfield County and even in the NYC area. However, we can also continue to build relationships and create virtual programming in consultation with campus offices in Storrs and at other campuses within the UConn system. Sharon Sobel, one of our Stamford FYW instructors, for example, has coordinated a series of virtual museum visits for her 1007 students with experts from the Benton Museum. And in a few weeks, Kara Flynn will virtually visit my classes to walk them through digitized materials from the Swing Journal Project Records that are held in Storrs but have been digitized for greater access.

Approach collaborations with a willingness to divide instruction to meet shared goals.

The combined strengths of you and your campus or community partner can really enhance the work done in the classroom. I do think it’s important to adopt an approach that’s more flexible in terms of sharing instruction and expertise. In my case, archival educators can find appropriate primary sources, explain document analysis to students via live meetings or prepared handouts, and assist with foundational research strategies. Meanwhile, I can inform the discipline-specific pedagogy, provide content information related to our course inquiry, and reinforce to students our broader learning objectives. Dividing instruction in this way closes the gap between multiple professions, models effective collaboration to students, and makes the classroom experience that much more valuable and engaging for students and instructors alike.

Consider the afterlife of the partnership.

From your earliest stages of brainstorming, think about the afterlife of the partnership. Is this a collaboration that you can turn into a service-learning course? Is it something you can continue to collaborate on via a conference presentation or publication? This suggestion emerges from my own editorial work. I currently serve as lead editor of Notes from the Field, an extension of the Teaching with Primary Sources (TPS) Collective. Notes from the Field is an online, peer-reviewed blog that highlights practical lessons and stories from the front lines of teaching with primary sources. Our authors write short articles that explore the theory and practice of teaching with primary sources—and we get pieces from all sorts of practitioners: librarians, archivists, teachers, and cultural heritage professionals. We try to highlight pieces that delve into and reflect on the productive partnerships that professionals in different fields forge with one another.

Realistically, developing the sorts of relationships and coursework we considered during the winter workshop is both time- and labor-intensive; it means extra work and can often mean navigating a lot of logistical complications to make sure that students are engaged in meaningful, relevant research and projects. If you can continue this work and have it result in a conference panel or publication, that’s certainly value added to the endeavor.

I will share below a few readings and resources that helped me as I prepared for the workshop and may prove useful to anyone considering the range of opportunities available to opening up their classroom to collaboration.

Readings and Resources

Engaging Undergraduates in Primary Source Research, ed. Lijian Xu (2021, Rowman and Littlefield)

Rockefeller Archive Center’s Archival Education Repository

Teaching with Primary Sources Bibliography: a chronological, user-generated bibliography for resources about Teaching with Primary Sources.

“Tips for Teaching Community-Engagement Projects in the College Writing Classroom,” by Bradley Smith (MLA Style Center)