by Ellen C. Carillo

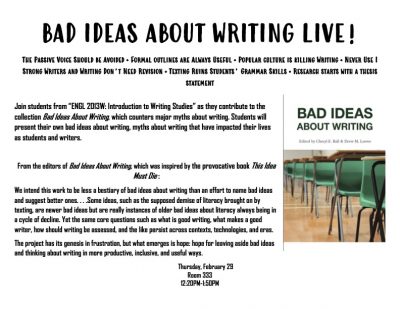

On February 29, on the Waterbury campus, I hosted an event titled “Bad Ideas About Writing Live!” The event featured the writing of students in ENGL 2013W: Introduction to Writing Studies. Students developed their own “bad idea about writing” and presented them before an audience comprised of staff, students, and OLLI (Osher Lifelong Learning Institute) members. As I discuss below, the sequence of assignments of which this “bad idea” was a part, would fit well within the first–year writing curriculum and specifically ENGL 1004 and 1007. Students seemed to enjoy the opportunity to write (and vent!) about something they have experienced as student-writers, and I encourage you, my colleagues, to use or adapt this sequence of assignments if it fits within the framework of your course.

You may be familiar with the 2017 open-access textbook/collection Bad Ideas About Writing. The book has also been recorded, and an audio copy is available here. Editors Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe describe their project as follows:

This collection is an attempt by a varied and diverse group of writing scholar–teachers to translate our specialized knowledge and experiences about writing for a truly wide set of audiences, most of whom will never read the scholarly journals and books or attend conferences about this topic because of the closed nature of such publications and proceedings. . . . We intend this work to be less a bestiary of bad ideas about writing than an effort to name bad ideas and suggest better ones. Some of those bad ideas are quite old, such as the archetype of the inspired genius author, the five-paragraph essay, or the abuse of adjunct writing teachers. Others are much newer, such as computerized essay scoring or gamification. Some ideas, such as the supposed demise of literacy brought on by texting, are newer bad ideas but are really instances of older bad ideas about literacy always being in a cycle of decline.

The editors situate their project as quintessentially relevant because “the same core questions such as what is good writing, what makes a good writer, how should writing be assessed, and the like persist across contexts, technologies, and eras.” Ball and Loewe concede that while “the project has its genesis in frustration. . . what emerges is hope: hope for leaving aside bad ideas and thinking about writing in more productive, inclusive, and useful ways.”

Before students could develop their very own bad idea about writing they needed to engage in a range of smaller, scaffolded activities that would make this final assignment most productive. I detail those assignments below and explore their relevance to FYW goals.

Assignment 1: Your Experiences With Bad Ideas About Writing

Students were asked to read (or listen to) the introduction to and browse the table of contents of Bad Ideas About Writing and then choose at least 2 selections to read/listen to from each of the 8 sections. This means they read 16 pieces total, which sounds like a lot, but each entry is only a few pages.

I instructed students to choose selections they are more likely to relate to because they, too, believed this bad idea or currently believe this bad idea about writing. They listed their selections and chose one to focus on in either an audio recording or written response. They responded to the following questions: Trace the origin of the bad idea for you personally. Where did you pick up this bad idea? Was it taught to you? Is it an idea you assumed was/is true? Is it an idea you came to understand through your experiences of writing? Through your experiences of being assessed on your writing? Detail how this bad idea has influenced you as a writer and student.

Assignment 2: Read Mike Bunn’s “How To Read Like A Writer”

Students read this piece to learn about the “reading like a writer” (RLW) strategy, so they could apply it in the next assignment.

Assignment 3: Group Work on Bad Ideas about Writing

After reading several entries from Bad Ideas about Writing for content and learning how to read like a writer, in small groups, students chose 3 entries in Bad Ideas about Writing to (re) read “like a writer” as it is defined in Bunn’s essay. They were reminded that this way of reading is appropriate because they will be writing their own entry in the same style. Once the whole group read these entries, they answered the following questions. They were invited to also draw on the other entries each one of them read for Assignment 1.

1st Submission: Bad Idea About Writing

Having completed this group work, students were ready to write a first submission (I prefer that term to “draft”) of their bad idea about writing. I have pasted an excerpt from theassignment below:

Drawing on what your group noticed about the style of the entries, compose a 750-1000-word entry (not inclusive of additional sections; more below on this) in the same style meant for the same audience. As we read, Bad Ideas About Writing is intended for “‘the public’ in all its manifestations—teachers, students, parents, administrators, lawmakers, news media” (1). The editors explain further, “These publics deserve clearly articulated and well-researched arguments about what is not working, what must die, and what is blocking progress in current understandings of writing. . . .This collection is an attempt by a varied and diverse group of writing scholar–teachers to translate our specialized knowledge and experiences about writing for a truly wide set of audiences, most of whom will never read the scholarly journals and books or attend conferences about this topic because of the closed nature of such publications and proceedings” (1-2). Unlike Doug Hesse’s piece and the other journal articles you perused in Module 1, this piece is meant for those largely outside of Writing Studies. Keep that larger audience—the public—in mind as you write your readable and jargon-free entry.

Don’t forget to include a section with recommendations for further reading, a list of keywords, and your bio. These should be in addition to the word count indicated above.

You are welcome but not required to cite outside sources throughout your entry.

Revising the First Submission

Before presenting their bad ideas at the event on February 29, students engaged in peer review, received feedback from me, and revised their bad ideas. They also revised with our writing workshop on revision, editing, and proofreading in mind.

Using This Sequence in FYW

This sequence of assignments would work well in a first-year writing course focused on education, such as the baseline syllabus, humans of education, or with any inquiry that addresses writing.

The initial work (assignment 1) wherein students chose which 16 selections across the more than 60 included in the collection involved collecting and curating. After doing so, students homed in on the one entry to which they would respond in that first assignment. As students engaged with these short texts—first the larger group and then their chosen entry—they connected these entries to their own knowledge of and experiences with writing in order to complete the first assignment.

Once students read Mike Bunn’s “How To Read Like a Writer,” (Assignment 2) they returned to these entries and engaged additional entries (Assignment 3) in a different way. They read like a writer to examine how texts present and develop ideas, including the moves a writer or text makes. They collaborated in small groups to do this work and then brought their findings back to the full class.

Students’ work with contextualizing is perhaps clearest through the ways in which they assessed, while reading like a writer, how the conventions associated with these entries were different from those associated with pieces we read earlier in the semester. Those earlier readings were about the origins and evolution of Writing Studies, were meant for those in the field, and came from edited collections and journals in the field. Students needed to, instead, draw on a different set of conventions to write their “opinionated encyclopedia entries,” as editors Ball and Loewe call the contributions, a set of conventions that are related to the general audience for which these entries are meant.

Students’ theorizing is best represented by the bad idea about writing each of one them developed. Although meant to stylistically imitate the entries from the published text, each student-authored bad idea about writing (first submission) constituted a new line of inquiry about a provocative subject.

Finally, students were positioned to think about circulation. First, a peer would read and respond to their entry during a peer-review activity, and then students would revise their entries and present their ideas live to a very real public, including UConn students, faculty, staff, and OLLI members.

This assignment—and the overall sequence, really—speaks to several of the learning objectives of first-year writing courses. Through this work, students are recognizing themselves as writers who make valuable contributions to a real project within Writing Studies. They were responsible for using writing to develop new ideas and discover new lines of thinking related to controversial and provocative ideas within the field. All students were participating in the conversation that is the collection Bad Ideas About Writing, and several directly cited and engaged with others who are also part of the conversation. Moreover, students’ “bad ideas” directly contribute to the field’s collective knowledge and understanding. Finally, students planned, reflected on, and revised their bad idea entries with a “general” audience in mind knowing they would present them in front of peers, faculty, staff, and OLLI members.

Students’ Bad Idea Entries and Audience Response

Students wrote on a range of subjects. The following are titles of just some of the “bad ideas” they shared at the event: “Good Sources Need to be From Databases;” “Poetry is Not that Important in Educational Writing;” “Wikipedia is Not a Reliable Source;” “The More Details the Better;” “Utilizing Advanced Vocabulary is Always Good;” ChatGPT is Gonna Ruin Writing;” and “You Must be a Tortured Artist to Be a Good Writer.” Students shared controversial points of view such as “educators should be advised to remove word count and/or prerequisite number of pages from their grading criteria” and “AI can help guide writers, give key points, and help writers think creatively.”

Their ideas were well received by audience members. Catherine Capua, an OLLI member, wrote to me after the event noting that “The topics were varied, challenging, and provocative. The students were thoughtful and engaged in their work. I came away with a sense of their commitment to writing and your commitment to teaching. It was a wonderful way to spend some time on the UConn campus.”

Final Thoughts

As an instructor, it was rewarding to hear students present their bad ideas about writing. Students seemed impressed with each other’s writing, too, as they had only read one of the peer’s entries. For the most part, students captured the style and feel of the entries from the published collection. By and large, each student chose a provocative subject, wrote in a colloquial and conversational tone, employed headings to help support readability, drew on personal experience, and composed engaging prose. Many students’ entries could easily be mistaken for the professional, published entries.

In fact, I was approached by the campus librarian after the event who noted we shouldpublish these in some way and add to the student collection over the years. I agreed and thought to myself that this would be a great opportunity not only to showcase students’ work but to think about circulation yet again in a different way.

I invite you, my colleagues across UConn campuses, to use or adapt this assignment, as well as to consider a collaboration on a related publication of students’ bad ideas about writing.